Why you can't handle disagreement anymore

If you’ve noticed that every argument feels personal now, you’re not imagining it.

Something has changed. Not just in politics or online discourse, but in how disagreement itself lands in your nervous system. Conversations that once allowed for curiosity or uncertainty have hardened into moral lines. People who question your views no longer feel like people offering a different perspective. They feel like threats.

This isn’t a political problem. It’s an identity problem. And it goes deeper than you think.

The conventional explanation is that we’ve become more polarized. That social media algorithms have trapped us in echo chambers. That bad actors are manipulating discourse. All of this is true, but it misses the point.

The real question isn’t why we disagree more. It’s why disagreement has become intolerable.

I want to share a framework for understanding what’s actually happening, why it’s happening to you specifically, and what you can do about it. This isn’t about changing your political views or becoming more “moderate.” It’s about understanding why your sense of self has become so fragile that a stranger’s opinion can ruin your afternoon.

Let’s begin.

I. The pattern I kept seeing

In the fall of 2011, during my final year as a chaplain at Harvard, tents began appearing in Harvard Yard.

What started as a loose echo of Occupy Wall Street quickly took on a life of its own. Students gathered daily. Signs multiplied. Conversations that had once taken place in classrooms moved into public space, charged with urgency and moral intensity.

Some of the students involved were people I already knew well. I had spoken with them about family, faith, anxiety, ambition, and purpose. They were thoughtful, curious, and often deeply idealistic. As the protests grew, many of them became visible leaders and organizers. Their days were reorganized around the movement. Their language changed. Their sense of self began to fuse with the cause itself.

What struck me was not the content of their political commitments. Reasonable people could disagree about the aims or methods of the Occupy movement, and many did. What stood out was how quickly disagreement ceased to feel like disagreement at all.

Students who questioned the movement were no longer perceived as people offering an alternative view. They were experienced as challengers to something far more personal.

For some of those involved, the movement had become an identity. To criticize it was not simply to argue policy or tactics. It was to threaten a newly formed sense of belonging and moral orientation. The emotional intensity of these exchanges seemed disproportionate to the age of the commitments themselves.

I remember sitting with one student who spoke with absolute certainty about what justice required, yet struggled to explain where that certainty was rooted. There was no appeal to a tradition, a community, or a long held framework of responsibility. The language was urgent and total, but also strikingly thin. The movement provided meaning, belonging, and purpose, but only so long as it remained unquestioned.

What I observed was not cynicism or manipulation. It was vulnerability. These students were not driven by bad faith, but by a hunger for orientation. In the absence of inherited structures that once shaped identity over time, the movement offered something immediate and powerful. It told them who they were, who stood with them, and who stood against them.

Eventually the encampments disappeared. The tents were removed, attention shifted, and the campus returned to something like its previous rhythm.

But the underlying pattern did not disappear with them.

II. The same pattern, different context

Less than a year later, I encountered the same structure in a very different setting.

As a congregational rabbi in Denver, my work unfolded within a thick communal framework. The synagogue was organized around a shared calendar, repeated rituals, and obligations that did not depend on individual preference. Time moved through weeks, seasons, and years rather than through news cycles. Communal life was designed to shape patience, continuity, and responsibility.

Yet even within that environment, political identity increasingly functioned as the dominant moral lens for many congregants. People remained affiliated, but the rhythms that once shaped moral imagination competed with a constant stream of political content. The shared language of communal discernment began to erode.

Then the Aurora movie theater shooting occurred.

Fear entered the congregation immediately and understandably. Grief was personal. Vulnerability was real. The question of safety could not be avoided. Yet the conversation that followed revealed how fragile shared moral language had become.

The specific issue of whether firearms should be permitted in the synagogue quickly escalated beyond practical considerations. For some congregants, opposition to guns in the sanctuary was framed as an absolute moral imperative. For others, the right to carry was treated as equally non-negotiable. Disagreement was not experienced as a difference in judgment, but as a challenge to identity itself.

What was most revealing was not the strength of conviction, but the displacement of communal reasoning. Long standing norms for collective decision making lost authority. Appeals to shared responsibility and pastoral care carried less weight than political alignment. Even within a community built around shared ritual, disagreement became existential.

The synagogue remained a place of gathering, but it struggled to function as a place of moral formation. Communal life persisted, but it no longer served as the primary framework through which difficult questions were navigated. Political identity had assumed that role.

These experiences clarified something essential. Polarization was not simply increasing. It was transforming. Disagreement had become intolerable because identity itself had become fragile.

And that fragility was not accidental.

III. What actually changed

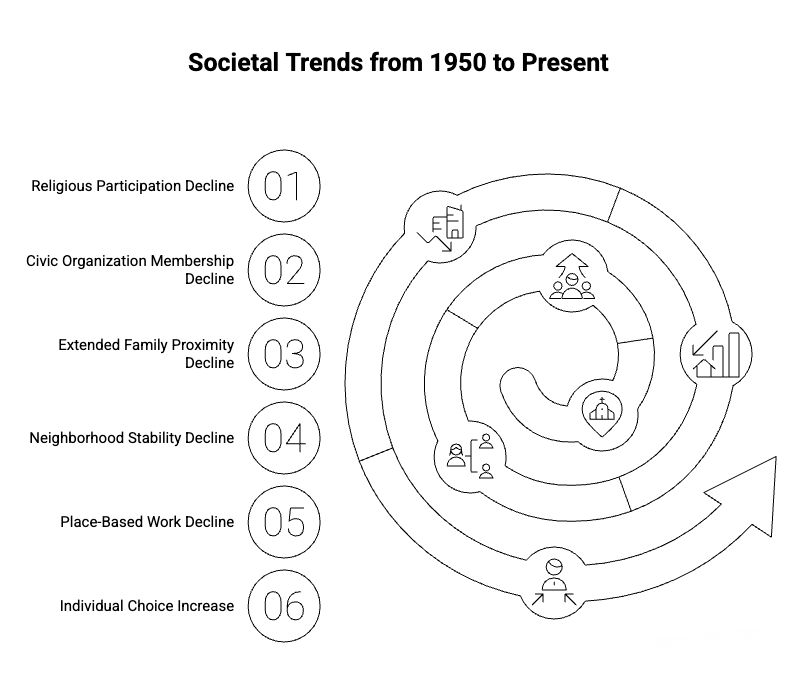

Beginning in the decades after the Second World War, Western societies underwent a series of shifts that slowly altered how individuals were formed.

Religious participation declined steadily. Civic organizations weakened. Extended families fragmented. Neighborhoods became more transient as geographic mobility increased. Work became increasingly specialized and detached from place.

These changes were not driven by hostility to community. Many were experienced as expansions of freedom. Individuals gained choice where earlier generations had obligation. They could leave inherited traditions, relocate easily, and define themselves through personal preference rather than communal expectation.

But freedom without formation carries costs.

The institutions that weakened were not merely constraining. They trained people to live with difference, to endure discomfort, and to carry responsibility beyond the self. They embedded individuals in narratives that extended backward and forward in time.

As these institutions eroded, identity became something assembled rather than received. Moral orientation became reactive rather than cultivated. Belonging became conditional, dependent on affirmation and alignment.

This is where the problem starts.

IV. Three things that look similar but aren’t

To understand what’s happening, you need to distinguish between three concepts that most people conflate.

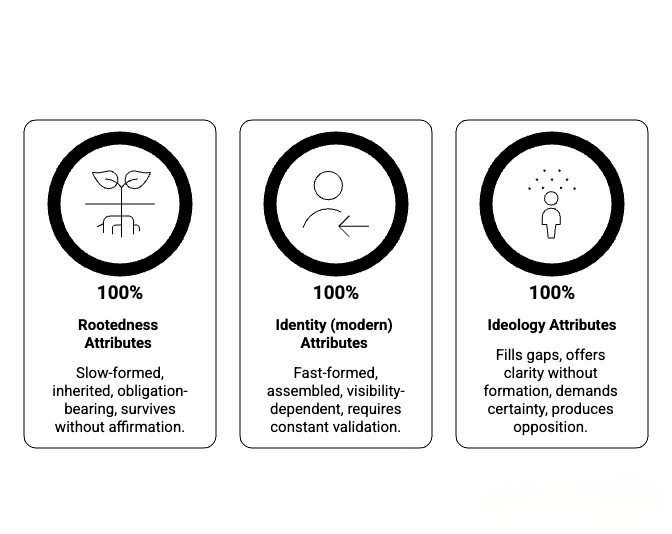

Rootedness is slow-formed. It is inherited, obligation-bearing, and shaped through repeated practice over time. It binds individuals to people, places, and histories they did not choose. It creates resilience because it does not require constant affirmation to survive. You don’t have to defend your roots. They simply are.

Identity, as it increasingly functions today, is fast-formed. It is assembled through affiliation, reinforced through visibility, and sustained through recognition. It promises meaning and belonging, but it remains unstable because it lacks continuity and obligation. It must be constantly performed and defended because it has no foundation independent of social validation.

Ideology often fills the gap when rootedness erodes. It offers moral clarity without formation and belonging without inheritance. It demands certainty and produces opposition because it cannot tolerate ambiguity without collapsing.

Modern political identities promise meaning, purpose, and belonging, but only so long as opposition remains constant. Disagreement becomes intolerable because it threatens the structure holding identity together.

What appears as moral certainty is often insecurity. What appears as passion is frequently a response to dislocation.

This is why arguing with someone whose identity is tied to a position feels so futile. You’re not actually arguing about the issue. You’re threatening their sense of self. And people will defend their sense of self far more vigorously than they’ll defend an idea.

V. The counterintuitive truth about openness

Here’s where the conventional wisdom gets it exactly backwards.

Western liberal societies largely assumed that social harmony required loosening attachment to inherited forms of belonging. Particular identities rooted in religion, culture, place, or tradition were treated as obstacles to neutrality and pluralism. The expectation was that as these attachments weakened, individuals would become more open, more tolerant, and more capable of coexistence in diverse societies.

The logic seemed sound. If people care less about their tribe, they’ll be less hostile to other tribes. If people aren’t attached to particular traditions, they won’t fight over whose tradition is correct. Reduce the intensity of belonging, and you reduce the intensity of conflict.

Yet as those attachments weakened, harmony did not follow. Instead, new and more brittle identities emerged to take their place.

These identities were thinner, more reactive, and more dependent on opposition. They offered belonging without obligation and meaning without inheritance, but they lacked the depth and resilience required to sustain disagreement. As a result, difference increasingly felt dangerous, and pluralism became harder rather than easier to maintain.

The central claim I want to make is counterintuitive but I believe it’s true.

Deep rootedness does not produce intolerance. It often produces openness.

Individuals who are securely grounded in a tradition, a community, or a shared history are better equipped to encounter difference without fear. They are less dependent on constant affirmation and less threatened by disagreement because their sense of self does not rest on continual validation. Their identity is not something that must be defended at every moment, but something that has been formed over time through practice, obligation, and continuity.

Rootedness provides a kind of moral ballast.

It allows individuals to engage disagreement without experiencing it as a destabilizing force. When people know who they are and where they come from, they are better able to listen, to tolerate ambiguity, and to remain in relationship even when conflict arises.

This does not mean that rooted communities are free of disagreement or tension. It means that disagreement does not automatically threaten the legitimacy of the person who holds it. Difference can be endured because belonging is not constantly at stake.

VI. Why technology makes this worse (but isn’t the cause)

Technology enters this story as an accelerant rather than a cause.

I spent a decade in communal and religious leadership, where identity was shaped through slow relationships, shared obligations, and repeated practices that accumulated meaning over time. Moral formation happened through presence, patience, and continuity.

I then moved into the technology sector, where I have spent another decade working within systems shaped by a very different ethos. These systems are optimized for engagement, immediacy, and constant reaction.

Experiencing these two worlds from the inside clarifies why digital platforms so effectively magnify identity fragility, reward moral absolutism, and intensify conflict in a culture already stripped of rootedness.

In communities formed through slow practice, you learn to live with people you disagree with. You share meals with them. You see them at weddings and funerals. You have to figure out how to remain in relationship across difference because leaving isn’t easy and the community would fracture if everyone left over every disagreement.

Online, none of those constraints exist. You can curate your social environment to include only people who affirm your views. You can mute, block, or unfollow anyone who challenges you. The friction of disagreement that once forced people to develop tolerance has been engineered away.

And the platforms themselves reward the behaviors that make polarization worse. Outrage generates engagement. Certainty performs better than nuance. Tribal signals get amplified while complexity gets ignored.

But here’s the key point: the technology is exploiting a vulnerability that already exists. If people had deep roots, they would be less susceptible to the engagement-maximizing incentives of these platforms. They would have an identity that didn’t depend on constant validation. They would be able to encounter disagreement without feeling threatened.

The platforms don’t create identity fragility. They reveal it and profit from it.

VII. What you can actually do about this

If the problem is loss of rootedness, the solution isn’t to become more “open-minded” in the abstract. That’s like telling someone with a broken leg to walk more carefully. The issue isn’t how you’re walking. The issue is that your leg is broken.

The solution is to rebuild the conditions that make genuine openness possible.

This isn’t about returning to some idealized past. It’s about being deliberate about what you allow to shape your identity.

Here’s a framework for thinking about it.

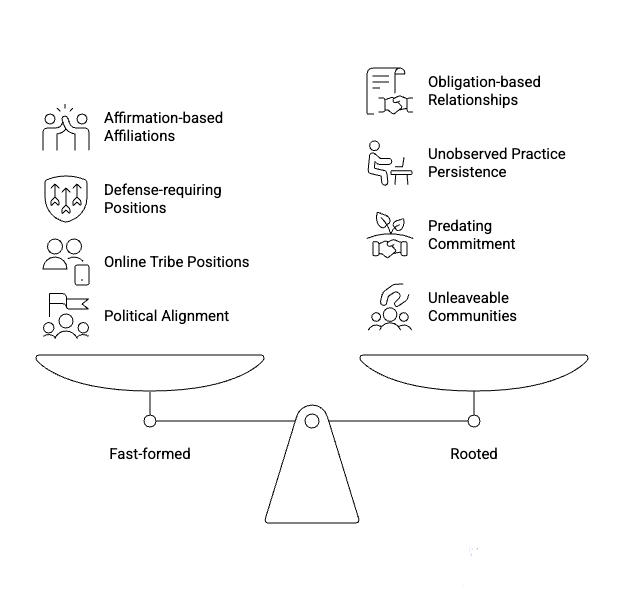

Audit your identity sources. Where does your sense of self come from? Make a list. Be honest. How much comes from political alignment? How much from online tribes? How much from things you did not choose but were formed by over time?

If most of your identity comes from things that require constant defense and validation, you have fast-formed identity. If most comes from relationships, practices, and commitments that would persist even if no one was watching, you have something closer to rootedness.

Seek out obligation, not just affiliation. The difference between rootedness and fast-formed identity is often the presence of obligation. Joining a community where you have responsibilities to others, where you can’t just leave when you disagree, where your belonging doesn’t depend on everyone affirming your views. This is increasingly rare, which is exactly why it’s valuable.

This could be religious community, but it doesn’t have to be. It could be extended family, a long-term neighborhood, a civic organization with actual commitments. The key is that the community makes demands on you, not just that it makes you feel good.

Practice staying in relationship across difference. This is harder than it sounds. The modern instinct when someone disagrees with you on something important is to conclude that they’re either stupid or evil and distance yourself. Rootedness requires resisting that instinct.

Find people in your life who hold views you find wrong or even offensive, and practice remaining in relationship with them anyway. Not by pretending you agree. Not by avoiding the topics. But by accepting that disagreement is a normal part of shared life, not a threat to be eliminated.

Be suspicious of certainty that arrives quickly. Remember the Harvard students whose moral certainty about the Occupy movement seemed disproportionate to how long they’d held those views? Fast-formed certainty is a warning sign. It usually means you’re using a position to construct an identity rather than arriving at a position through genuine inquiry.

When you find yourself feeling certain about something you learned about recently, ask yourself: am I certain because I’ve thought deeply about this, or am I certain because certainty feels good and aligns me with people I want to be aligned with?

Engage history as inheritance, not ammunition. Rooted identity includes a relationship with the past that isn’t simply about finding evidence for positions you already hold. It means accepting that you’re part of something that began before you and will continue after you, and that this shapes who you are whether you like it or not.

This is uncomfortable because the past contains things we now find wrong or shameful. But rootedness doesn’t mean approving of everything your ancestors did. It means accepting that you’re connected to them, shaped by them, and responsible for carrying something forward.

The paradox at the heart of this

I’ve spent years watching communities form and dissolve, watching people construct identities and defend them, watching disagreement turn into dissolution.

The pattern is consistent. The less rooted people are, the more defensive they become. The more their identity depends on external validation, the more threatening disagreement feels. The more they try to protect their sense of self, the more brittle it becomes.

And the inverse is also consistent. The most genuinely open people I’ve known, the ones who can engage difference without fear, who can listen without defending, who can change their minds without falling apart, are almost always people with deep roots. Not because their roots gave them the right answers, but because their roots gave them a self that didn’t need constant protection.

This is the paradox: openness is not achieved by shedding roots, but by sinking them more deeply.

If you want to become someone who can handle disagreement, who can engage with people who see the world differently, who can remain in relationship across difference, the path isn’t to care less about things. It’s to build a self that doesn’t require constant defense.

That’s slow work. It happens through practice, not insight. Through showing up, not optimizing. Through accepting obligation, not maximizing choice.

But it’s the only path that actually works.