The developer who doesn't code: what actually matters in 2026

Is learning to code dead in 2026?

I started as a bootcamp grad in 2017. Months of Ruby and JavaScript, portfolio projects, and a lot of hope. That path worked. I got hired, learned on the job, and built a career.

But I watch what’s happening with Claude Code and tools like it, and the pace is staggering. People are shipping hobby projects in an afternoon that would have taken me weeks. Non-technical founders are building MVPs without hiring a developer. Solo creators are launching startups that would have required a team of five just two years ago.

If you’re thinking about becoming a developer today, you’re probably wondering: is it even possible to start from scratch anymore?

The answer is yes. But not the way I did it. The skills that got me hired in 2017 are now table stakes that a $20/month tool can replicate. What matters now is everything that tool can’t do.

The skill that’s losing value fast

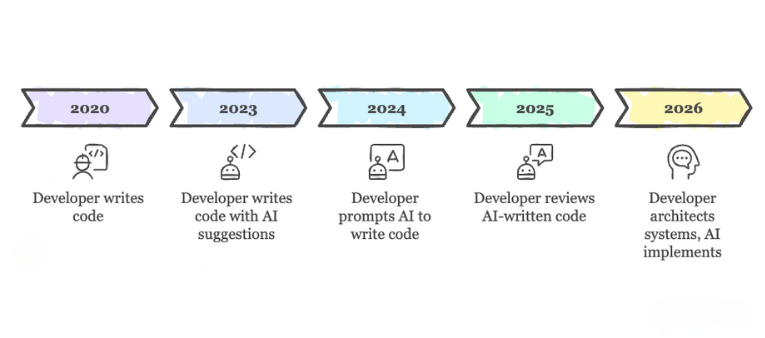

Writing syntax is becoming automated. If your value proposition is “I can write a React component” or “I know Python,” you’re competing with a tool that costs $20/month and never sleeps.

The raw act of translating logic into code is no longer scarce. GitHub Copilot, Claude Code, Cursor, and dozens of other tools can produce functional code from natural language descriptions. They make mistakes, sure. But they’re getting better every quarter while the skill of “knowing syntax” stays static.

This doesn’t mean developers are obsolete. It means the job is shifting. The question isn’t whether you can write a for loop. The question is whether you know why you’d choose one data structure over another, or why your architecture won’t scale past 10,000 users.

What the agents can’t do (yet)

I’ve seen where coding agents fall short (at least for now), here’s what they consistently struggle with:

They optimize for the immediate request, not the system. Ask Claude Code to add a feature and it will. Ask it to add that feature in a way that doesn’t create technical debt, and you’ll need to specify exactly what that means. The agent doesn’t know your codebase’s patterns, your team’s conventions, or your scaling requirements unless you tell it.

They’re also weak at:

- Predicting performance bottlenecks before they happen

- Understanding the operational cost of their architectural choices

- Designing systems that will need to evolve in unknown directions

- Reasoning about failure modes and edge cases at scale These gaps aren’t bugs. They’re fundamental limitations of tools that generate code without understanding systems.

Software design: the meta-skill

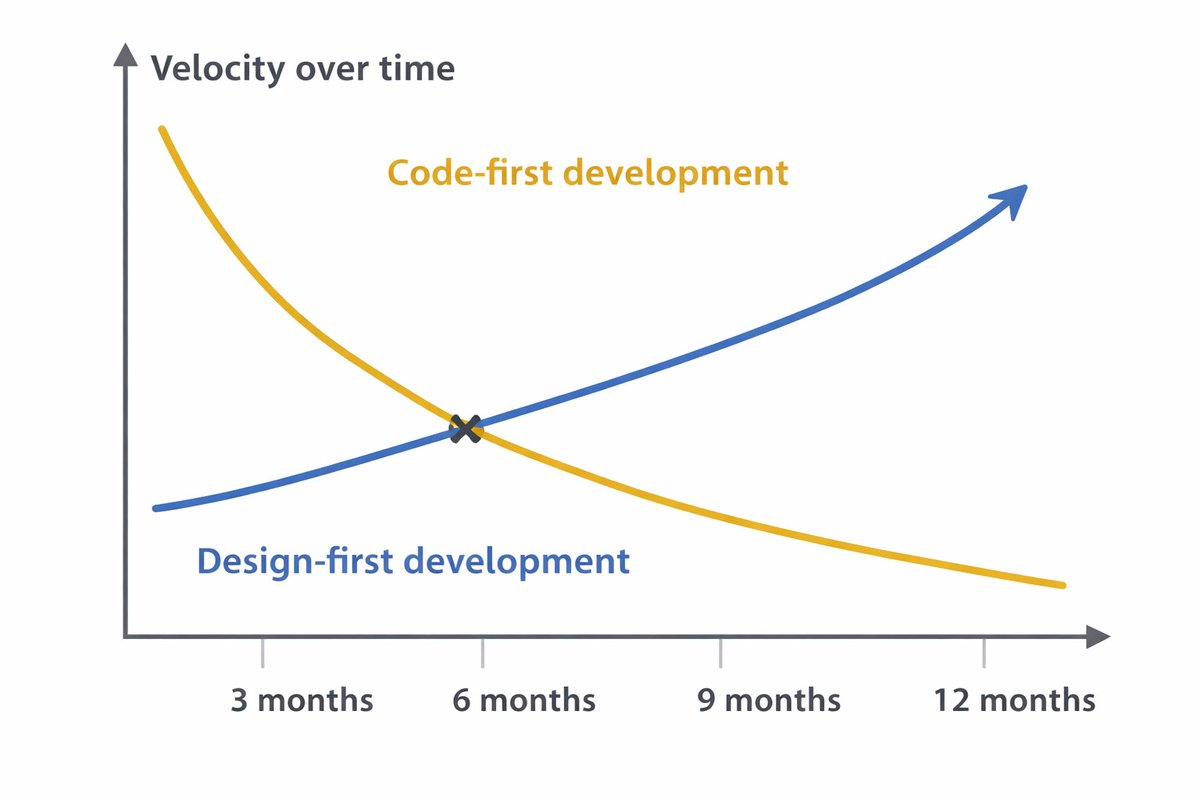

Software design is deciding what to build before you build it. It’s the difference between “this feature works” and “this feature works and won’t break everything else when we add the next ten features.”

Good software design means your codebase gets easier to change over time, not harder. This is counterintuitive. Most codebases accumulate complexity until adding anything new becomes painful. Design is the discipline that prevents this.

The concepts here aren’t new. SOLID principles. Domain-driven design. Clean architecture. Event sourcing. These ideas have been around for decades because they work.

What’s new is their importance. When you’re writing every line yourself, bad design just slows you down. When an agent is writing code at 100x your speed, bad design means you’re generating technical debt 100x faster.

Infrastructure: where code meets reality

Your application doesn’t run in a vacuum. It runs on servers, in containers, behind load balancers, connected to databases, cached at edges, logged, monitored, and billed by the millisecond.

Understanding infrastructure means understanding the real cost of your decisions. That elegant recursive function? It might cost $3,000/month in compute when it hits production. That simple database query? It might take 30 seconds when your table has 10 million rows.

Coding agents don’t think about:

- Whether your cloud bill will explode when traffic spikes

- How your system behaves when Cloudflar (again)

- Whether your architecture can actually be deployed by your team

- What happens to your data when a node fails mid-transaction Infrastructure knowledge lets you specify constraints that prevent expensive mistakes. “Write this function” becomes “write this function knowing it will be called 10,000 times per second and each call costs $0.000001 in compute.”

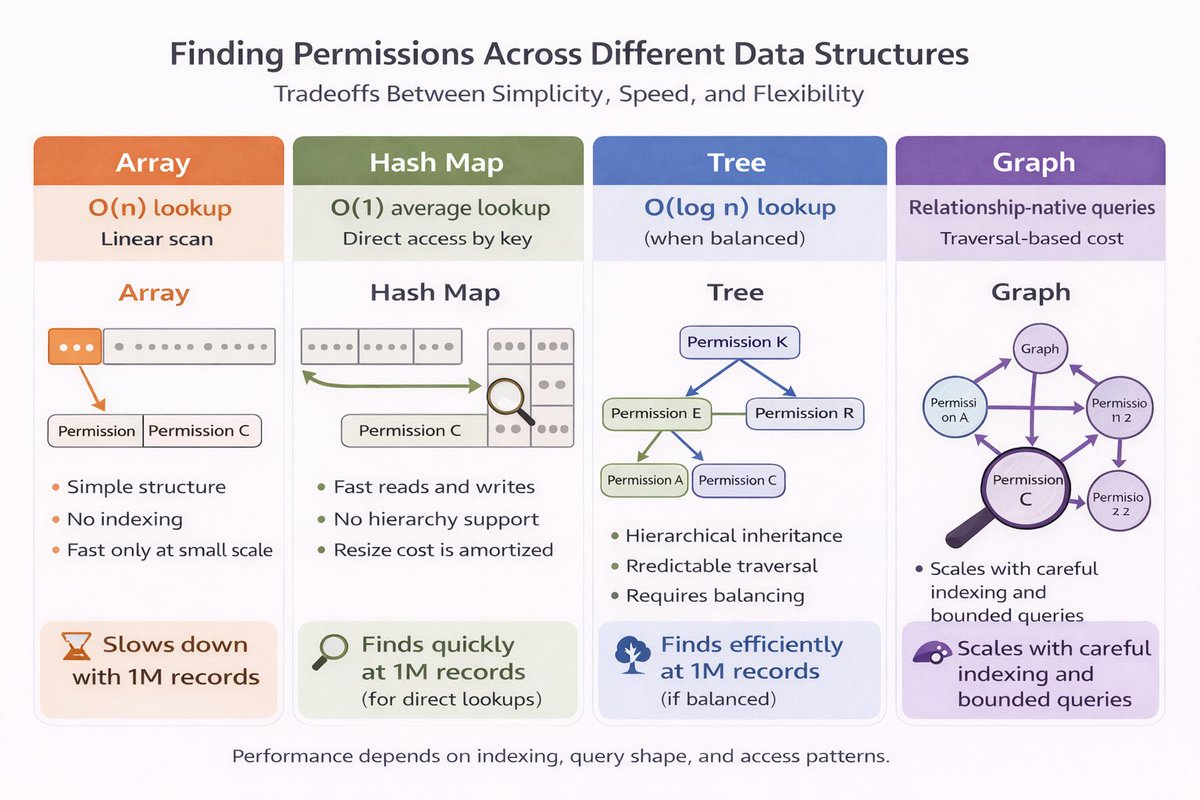

Data structures: the performance foundation

Here’s a test: your application needs to check whether a user has permission to access a resource. You have 1 million users and 10,000 resources. How do you structure the permissions data?

The answer depends on:

- How often permissions are checked vs. modified

- Whether you need to answer “what can this user access?” or “who can access this resource?” or both

- Your latency requirements

- Your memory constraints

- Whether permissions change in real-time or batch Choosing the wrong data structure can make your feature 1000x slower. The code to access data might be identical. The structure underneath determines whether that access takes 1ms or 1 second.

Coding agents will use whatever data structure seems obvious for the immediate task. They won’t ask whether an array, a hash map, a tree, or a graph better serves your access patterns at scale.

Performance: the constraint that changes everything

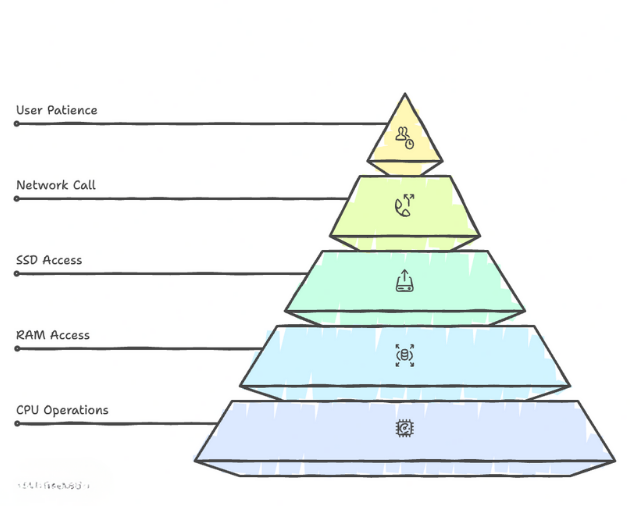

Performance isn’t about making things fast. It’s about understanding the constraints your system operates under and designing within them.

A senior developer thinks about performance before writing a single line of code. Not premature optimization. Awareness of the physics of computing: network calls take time, disk is slower than memory, memory is slower than CPU cache, and everything costs money at scale.

Consider these real constraints:

- A network round trip is 1-100ms depending on where your servers are

- Reading from disk is 1000x slower than reading from RAM

- A database query that scans a full table gets slower every day as data grows

- Mobile users on have latency issues before your server even responds When you prompt a coding agent, you can specify these constraints. But only if you know they exist.

How to actually learn this

Reading about software design doesn’t make you good at it. You need to build systems, watch them break, and fix them.

Here’s a learning path that works:

Build something real with an agent, then analyze what went wrong. Use Claude Code or Cursor to build a full application. Deploy it. Load test it. Watch what breaks. The failures will teach you more than the successes.

Study existing architectures. Pick open-source projects you admire and read their code. Not the features. The structure. How do they organize files? How do services communicate? How do they handle failure?

Learn one thing deeply before going wide. Pick PostgreSQL and learn it thoroughly before touching Couchbase. Pick AWS and understand it before adding GCP. Depth beats breadth for building intuition.

Read the boring stuff. “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” by Martin Kleppmann. “Fundamentals of Software Architecture” by Mark Richards and Neal Ford. These two books will teach you more than 50 tutorials.

The new developer job description

In 2026 and beyond, the developers who thrive will be:

System thinkers who understand how components interact, fail, and scale. They’ll spend more time on whiteboards than keyboards.

Constraint specifiers who can tell an agent exactly what “good” looks like for their system. Performance budgets, cost limits, reliability requirements, security constraints.

Quality judges who can review agent-generated code and spot the problems that aren’t syntax errors. The architectural decay. The performance time bombs. The operational nightmares.

The bottom line

Coding agents are tools. Powerful ones. But tools amplify the skill of the person using them.

A developer who understands software design, infrastructure, data structures, and performance will use Claude Code to build systems that actually work at scale. A developer who only knows syntax will use Claude Code to generate technical debt faster than ever before.

The question isn’t whether AI will change development. It already has. The question is whether you’ll be the person directing the AI or competing with it.

If you’re just starting out, spend 20% of your time learning to prompt agents and 80% learning the fundamentals they can’t replace. That ratio will serve you well going forward.

What’s the first fundamental you’re going to tackle?